Transforming Desire into Liberation: Practical Wisdom from the Second Noble Truth

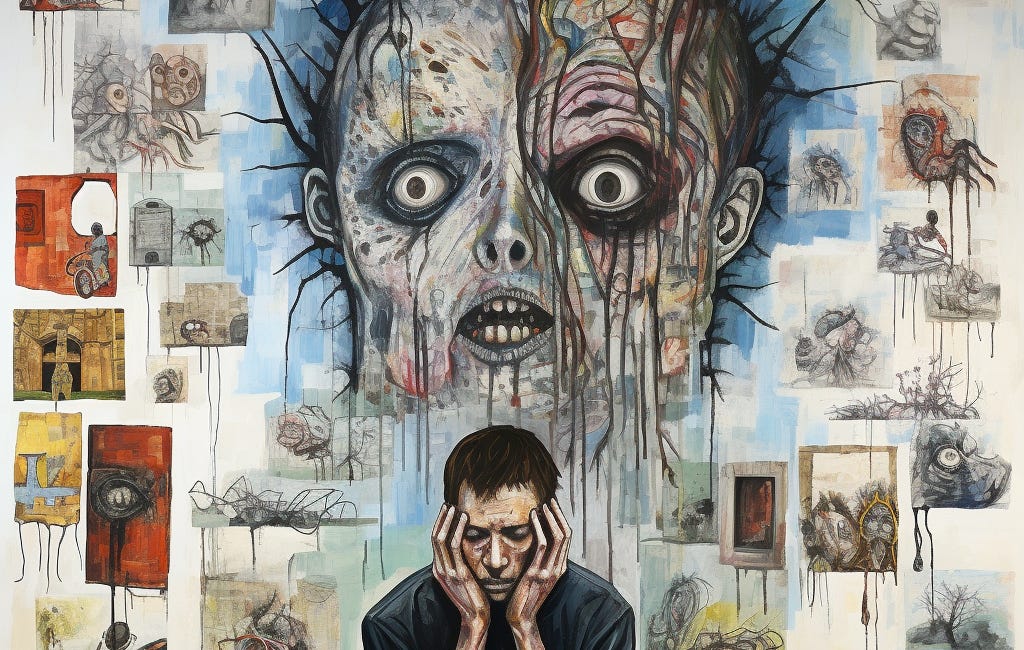

Understanding the nature of selfish desire, craving, and attachment is fundamental to discovering relief from suffering.

Ignorance is Bliss?

Cypher in the movie The Matrix, decided it was preferable to live a life of illusion than endure the harsh truths of reality.

The matrix had pleasures, and people could delude themselves into believing they are important, powerful, and loved and admired by others—even if none of it were true.

In the short term, ignorance has benefits. Fleeting satisfaction from worldly pleasures briefly satisfies the mind. However, satiation is short-lived, and the longing for more and dissatisfaction returns over and over again. Further, if worldly pleasures are lost and unavailable, people suffer from the longing for what they can’t have.

Worldly pleasures are always short-lived. If a person jumps off a tall building under the ignorant delusion that they can fly, it will be a blissful flight followed by a deadly crash.

Ignorance is Pain

In the First Noble Truth, the Buddha identifies dukkha, or suffering, as the cause of all human problems.

In the Second Noble Truth, the Buddha teaches us to “abandon origins.” Known as "The Truth of the Cause of Suffering" or "Samudaya," the Buddha states that the mind causes suffering.

The Second Noble Truth identifies the root cause of suffering as "tanha," which translates to craving, attachment, or desire. It asserts that the fundamental reason people experience suffering is their insatiable and clinging desires for objects, people, and even their “self.”

He further identifies the reason the mind continually makes this harmful mistake is due to ignorance of the true nature of reality.

We falsely attribute qualities to objects and people and form attachments to them because we believe they will satisfy us and make us happy.

We believe the qualities of these objects or people are inherent, as if these positive qualities exist outside of our mind and our perceptions and reside in the object or person.

This is not what way things are.

The Gods must be crazy

The reality of objects doesn’t exist outside of our minds.

Yes, there is often stuff there, matter that our bodies will react to if our senses make contact with it, but every characteristic of that object is a construct of our mind.

To illustrate this point, watch the scene from the movie The Gods Must Be Crazy, where a Kalahari tribesman discovers a Coke bottle.

Watch this scene and carefully consider its meaning.

The tribesman had no concept of a Coke bottle. It wasn’t part of his reality.

When he discovered the object, he brought it back to his tribe to figure out what it was and what it could be used for.

They constructed an entirely new reality where a carelessly discarded Coke bottle became a precious resource.

That scene illustrates humorously the relative nature of reality. The world outside of this man’s tribe knows the “reality” of a Coke bottle, but he and his tribe do not.

They take an unknown outside object, determine its characteristics, and create their own “reality” consistent with their experience. Yet, the tribe’s reality has almost no congruence with what the rest of humanity believes to be the truth about the Coke bottle.

If the Coke bottle, or any object, had intrinsic qualities inherent to the object itself, we would all recognize the object for what it is.

If we can’t be certain of the reality of a Coke bottle, what can we be certain of?

The Primordial Error in Buddhism

At some point in the development of a human fetus, historically called a quickening, a perceiving consciousness comes into existence. Shortly thereafter, this new consciousness becomes aware of its own existence.

At the moment of self-awareness, consciousness makes two conclusions:

I exist.

I am important.

With self-awareness, we give birth to Selfish Desire, our instinct to survive, and other primal forces needed for individual survival.

We typically spend the remainder of our lives grasping at our “self” as if it exists intrinsically, independent of the mind and body that generates conscious awareness.

This is the primordial error. The fundamental mistake the Buddha exhorts us to correct.

If we can overcome the error of self-grasping ignorance, then we no longer grasp at objects of desire, our craving stops, and our suffering comes to an end.

Unfortunately, that’s easier said than done.

Pounding the boulder of emptiness

In my opinion, meditating on emptiness is like pounding a large boulder in an attempt to break it down.

If one pounds on a large boulder with a sledgehammer, the boulder can take blow after blow without showing any damage. It’s easy to believe one isn’t making any progress, particularly when the boulder appears unfazed by the pounding.

However, deep inside the boulder, small cracks are forming, fissure lines forming, and the boulder is weakening.

Session after session spent meditating on emptiness is like pounding a large boulder. It seems like no progress is made, but eventually, after enough pounding, the boulder cracks, often shattering into many smaller pieces.

The smaller pieces are residual errors, places in the mind where the truth of emptiness hasn’t fully penetrated.

The first major breakthrough with emptiness provides tremendous feelings of clarity and inner peace, but any fragments that remain will disturb that peace and cause you to grasp once again.

The meditations on emptiness must continue until every small rock is crushed, and no event, no person, no desire has the power to induce grasping.

Parallel paths to cessation

The Second Noble Truth identifies the fundamental reason people experience suffering is their insatiable and clinging desires.

Buddhist practitioners often take a twofold approach to combatting the origin of suffering. One is meditating on emptiness, as described above, and the other is meditating on the faults of craving, attachment, and desire to lessen the tendency to do so.

By acknowledging and understanding the cause of suffering as attachment and craving, practitioners can work towards reducing these mental habits, practicing mindfulness, and ultimately moving toward the Third and Fourth Noble Truths, which offer the path to the cessation of suffering and the attainment of liberation (Nirvana).

First Meditation on the Second Noble Truth

Tibetan Buddhist Lamrim does not provide specific meditations on the Four Noble Truths. In fact, the entire intermediate scope has only one meditation, the desire to attain liberation from Samsara.

However, the intermediate scope is based on the teachings of the Four Noble Truths, and many subsequent commentaries from Buddhist masters provide meditations on those.

This first meditation is based on the fundamental teachings of the Second Noble Truth.

Contemplation

Consider what you read in this post and focus on the following first-person narrative:

My selfish desires for pleasure, status, objects, and people are sources of craving. My cravings form attachments. My selfish desires, cravings, and attachments are the sources of all my suffering.

Object of Meditation

The contemplation gives rise to a determination to abandon selfish desires, cravings, and attachments.

You should hold this determination in your mind for as long as possible.

Second Meditation on the Second Noble Truth

In the book Modern Buddhism, Geshe Kelsang Gyatso offers a meditation on abandoning origins. It addresses the core problem of the emptiness of self directly.

Contemplation

Consider what you read in this post and focus on the following first-person narrative:

I must apply great effort to recognizing, reducing, and finally abandoning my ignorance of self-grasping completely.

Object of Meditation

We should meditate on this determination continually and put our determination into practice.