Floating Through the Mind: My Journey of Self-Discovery in a Float Tank

How I came to spend several hundred hours in a float tank practicing Tibetan Buddhist Lamrim.

A personal journey

From the time I was very young, I observed the activity of my mind.

When I was three or four years old, I remember several occasions when I lay in bed and noticed this odd feeling of existential angst. I noticed that I had a body; it limited me and defined me. It wasn’t a pleasant feeling like I joyously figured out who I was. It was unsettling because I had an intuition that I was something more.

As I grew and developed, I displayed certain advanced skills. I was highly physically coordinated, and I scored in the 99th percentile on standardized tests.

My family liked playing games, and I found I could focus concentration for very long periods, obsessively at times.

I was not unusual in that respect. Many children can control their mental focus and sustain it for long periods when they are fascinated by some activity. Even my autistic son has mastered many video games and exhibits these traits.

I found it satisfying to master games, but I often quit playing them after achieving mastery. When I was nine years old, I discovered a game I couldn’t master: golf. I’ve been playing it ever since.

Golf is Life

I love Golf.

My father set me loose to wander the Sacred Links at age 9. My grandfather maintained the grounds.

Golf intrigues me because it’s a rare competitive sport where the actions of your opponent don’t impact your outcome. It isn’t a miniature simulation of war, like most of our popular entertainment.

Golf is you against yourself.

It’s a perfect mirror of your inner life.

Over the years, it became a disciplined part of my spiritual practice.

If you want to know a person’s character, observe them for a round of golf, and all will be revealed.

Pilgrimage to Pebble Beach Golf Links in 1997

The world is not enough

When I was 18 years old, in the spring semester of my senior year, I only attended classes in the morning. My afternoons were free to play and practice golf, which I did every day.

I distinctly remember one afternoon, after practicing and playing nine holes, I sat in my car and looked out at the links, feeling empty and dissatisfied.

By all standards, I should have been ecstatically happy. I was playing the best golf of my life, I was about to graduate high school with honors, I had been accepted to a variety of colleges with many scholarship opportunities, and my personal life was full of friends, fun, girls, and good times.

There was no reason at all that I shouldn’t have been experiencing complete bliss and fulfillment, yet I wasn’t. I knew I could get better at golf, I noticed my financial circumstances weren’t as affluent as others, I had endless drama with girlfriends, friends, and family, and I had anxieties about the future.

My mind was powerful, and I had developed the ability to concentrate intensely, but my mind not disciplined in any meaningful way that provided peace, contentment, and happiness—and I knew it.

What was worse, I had no idea how to overcome it.

Failure of Religion

I was raised a Roman Catholic, but like many others, I found the faith overly focused on control and compliance and lacking in any spiritual meaning, so I rejected it all and considered myself an atheist for many years.

My family moved to the fringe of the Bible Belt when I was eleven years old, and I was exposed to Evangelical denominations that I found even more spiritually vacuous. It convinced me that organized religion, particularly Western religious traditions had no answers for me.

If I were to solve my mental and emotional problems and find true and abiding happiness, I believed I wasn’t going to find it in religion, particularly Western religion.

Philosophy and “The Answer”

I became interested in philosophy and debate, taking college courses on the subject and thinking about these issues. Like many others, I pursued the Holy Grail of instant enlightenment, as if a single thought or realization, perhaps found in a book, could relieve me of my emotional struggles.

If I could only find that one fact, I would be cured, made whole and happy, or so I thought. I applied my intellect to the problem and looked fruitlessly for answers.

I realized philosophy posed many questions, but it was always light on answers. I learned many arguments for and against God, religion, the afterlife, and so on, but each time I reached a conclusion, I knew it was wrong or incomplete.

Like most people, I had heard about Buddhist Enlightenment—and like most people, I had no idea what it was or how to achieve it.

It suggested to me that there was a specific epiphany, a moment of clarity caused by a single thought or idea. If I could only find “the secret,” I could be permanently happy and completely fulfilled all the time.

It was like reading E=MC2 and believing I somehow would understand all the physics that equation represented.

It never occurred to me that the Buddha’s enlightenment came after years of focused meditation practice and required numerous other realizations and mental disciplines to attain.

In my opinion, many New Age seekers carry the same erroneous belief that a single fact or realization can erase dozens of deeply engrained poor mental habits permanently—instant enlightenment. It doesn’t work that way.

I found Eastern thought fascinating, particularly Zen Buddhism and Taoism, because the writings were enigmatic, suggesting the answers were inside of me, somewhere already buried in my mind.

I turned to meditation to explore my mind to see if I could somehow gain control of it and tease out the answers for myself.

I was finally on the right track, but I had no idea how much work it would take or how long it would be before any meaningful results would become apparent.

The call of the mystic

When I was in my early teens, I watched the movie Altered States, a horror film based loosely on the life of John C. Lilly, who, among other accomplishments, invented the floatation tank to explore consciousness in complete sensory deprivation.

This scene was inspiring to me.

I’m naturally inclined to adventure. I explored uncharted caves as a teenager, took off on aimless road trips, and experimented with psychedelic drugs, marijuana, and anything else that looked exciting and perhaps a bit dangerous.

Star Wars excited me because it posited the idea that people could develop special skills based on their mind and mental focus. When the lead character in Altered States regressed to a dangerous primal state, I found it piqued my curiosity even more rather than deter me as a cautionary tale.

At a deeper level, I wanted to understand my “self,” and who I was; I believed my pathway to understanding was through studying the mind. I still do.

Years later, a float tank center opened near my house that offered an unlimited membership. I scheduled daily float sessions at 6:00 AM to meditate for one hour in total sensory deprivation before going to work.

I didn’t know what I would encounter there, but I believed I would learn something about my mind and about myself.

I wasn’t disappointed.

Meditation and Monkey Mind

Before I embarked on my journey into my mind, I had experience with meditation. I didn’t have a periodic or committed practice, but over the previous years, I had learned basic techniques and knew what to expect during a mediation session.

Unsurprisingly, I experienced the cacophony of thoughts known as “monkey mind.”

Ordinarily, monkey mind is one of a range of distractions during meditation, but in sensory deprivation, monkey mind takes center stage, and like the star of the show, it grabs a microphone and loudly announces itself.

Monkey mind is not a real problem or a special phenomenon. In reality, monkey mind is the result of an increased awareness of the cacophony of thoughts continuously and simultaneously being processed by the mind all the time.

Mostly, mental processing occurs beneath the level of conscious awareness and direct attention. Conventionally, we refer to this as the subconscious mind. The only reason it’s subconscious is because our attention is generally focused on only one of these thoughts, and most people exercise little control over their attention.

The stream of consciousness is like riding a wild horse that’s difficult to tame or direct in a focused way. The mind’s attention diverts from one thought to another, one feeling to another, without being aware of all the other thoughts and feelings occurring at the same time.

Monkey mind is the competition among thoughts for conscious attention. Meditation is often on an object the mind doesn’t consider important, like the breath. While breathing is obviously important, the body does this autonomically, so the mind has no need to pay attention to it; thus, the mind is easily distracted by thoughts deemed to be more important.

Monkey mind is overcome in meditation through conscious effort. Basically, my determination to focus attention on the breath is deemed most important, and my unruly mind is forced to keep attention on it. The more I practice this, the more cooperative my mind becomes, and monkey mind is less of a problem to control.

After pushing through the distractions of Monkey Mind, I found a space of quiet where I could detach from the thoughts and observe them from afar.

A higher level of consciousness

I could observe a thought, like a cloud passing across the sky. In that state of observation, I realized I did nothing to generate that thought.

I couldn’t start it, stop it, or control it. The thoughts and feelings in my mind seemed to operate on their own, outside of my direct control.

People tend to believe they control their thoughts and rule their own minds because they can, to some degree, control their attention. But anyone who practices mindfulness meditation quickly comes to realize they can observe their thoughts, and direct their attention to some degree, but they have little or no control over what they actually think or feel.

We are not godlike rulers over our own mental domain. We are more akin to a Prime Minister trying to manage a Parliament of unruly representatives, each championing its own agenda.

As I reflected on this observation, I felt a sense of detachment from my thoughts and feelings. I was able to observe them from afar without identifying with them. I realized I was not my thoughts or my feelings but an observer of them.

The viewpoint of the observer of mental activity is one level removed from the activity itself. I had found a higher level of consciousness. Not in an intellectual, conceptual way, but in my direct experience.

Some meditators seek to observe the observer, and even observe the observer who observes the mind, and infinite regression seeking higher and higher levels of consciousness.

Some meditators attempt to observe the empty space of awareness itself where this activity takes place. The analogy is that thoughts and feelings are like clouds crossing the sky, and the task is to observe the sky itself to understand the nature of the empty space in the mind.

Perhaps these are mental mind games, products of an overactive imagination, but when I explore these states, I find a palpable feeling of understanding and intuition that leads me to believe I am experiencing something fundamental, as if there is something important in that nothing.

Words fail to capture these states. The only way to know them is to experience them for yourself.

Suppressing thoughts

In the few years prior, I spent much time listening to Eckhart Tolle on my daily commute, so his teachings influenced me to reduce or avoid conceptual thought.

I tried to suppress monkey mind, and I became convinced that it couldn’t be done.

Thoughts can be suppressed for a time, but it’s a constant and neverending battle that takes all my concentration. Suppressing thought is a meditation on itself, and I only really felt that I was ignoring thoughts rather than preventing them from arising.

Invariably, quiet thoughts would creep in.

I would notice I had suppressed thought, which was a thought.

I would congratulate myself for suppressing thought, which was a thought.

I would comment on my observations, rather than observe them.

The thought would arise, your mind is so quiet.

No matter what I did, the thoughts would keep coming. If there was a method for quieting my mind, suppressing thoughts was not it.

Further, while I felt a bit more peaceful without so many disturbing thoughts, in reality, I hadn’t done anything to clean up my mind.

The disturbing thoughts were still there, buried in my subconscious mind, outside of my awareness, where they still arose when triggered.

I was not liberated from my troubling thoughts; I had made no changes to my psychology; In short, I accomplished nothing.

Perhaps someone with many more years of thought suppression may report significant changes, but I became convinced it was a spiritual dead end.

In my opinion, a quiet mind is a side effect of a pure mind. As I became more advanced in my meditation practice, my mind certainly became less raucous, quieter, and more peaceful—not because I suppressed thoughts, but because I learned to ignore the unimportant ones, and they finally stopped arising on their own.

I have come to believe that learning how to devalue thoughts, judgments, and opinions is the essential step toward quieting the mind and reducing anxiety. Disturbing thoughts have the power to disturb us because we imbue them with truth and certainty.

It’s preferable, and easier to undermine a disturbing thought rather than ignore it or suppress it.

Let me provide a simple example to illustrate and make this abstract concept more concrete.

Think back to an incident where a driver cut you off in traffic, nearly causing an accident. These incidents trigger primal protective scripts that will disturb your mind no matter how advanced your spiritual practice. The key is what you do next.

Trying to determine the “truth” of the driver’s motivations is irrelevant. Making a judgment and becoming certain that your judgment is absolutely correct is counterproductive. The goal is not to become God and dispense righteous judgment. The goal is to reinstate your peace of mind.

An undisciplined mind will take this initial incident and react angrily toward it. The driver will be characterized as a rude and inconsiderate asshole with no redeeming value. This will make the person angrier, and then they will want to retaliate, flip the bird, or go full road rage and desire escalation to violence.

A disciplined mind will find ways to diffuse the situation as quickly as possible. Perhaps the driver was merely unattentive or distracted by something else. The incident could have been due to ignorance rather than malice. Even if the driver was a selfish and inconsiderate ass, then they are suffering from their delusions, and we should feel compassion for their negative state of mind.

An undisciplined mind will take small disturbances and make them larger ones. A disciplined mind will squelch small disturbances as quickly as possible. An undisciplined mind is a disturbed mind. A disciplined mind is a peaceful one.

Suppressing the disturbing thoughts won’t make them go away. It may stop the escalation, but the disturbance remains. Undermining the disturbing thoughts ends the disturbance permanently.

Parallel versus Serial processing

Your brain is a powerful parallel processor.

It processes thousands upon thousands of feelings and thoughts simultaneously, all day, and all night when you are not in Delta sleep.

Your consciousness is a serial processor working on top of the parallel one.

Consciousness presents the most important (highly emotionally charged) of these parallel ideas to the perceptual field that “You” identify with.

This presentation is sequential; thus you experience a “stream of consciousness.”

Why is this important?

Because 99% or more of your mental activity is happening behind the scenes, beneath the level of your conscious awareness.

These feelings and thoughts motivate most of your behavior and determine your moods.

It’s perilous to ignore what’s happening in your subconscious mind.

Moody Blues

Your mood is the sum total of the feelings being generated by your mind’s processing every thought, simultaneously, all the time.

If your mind is full of negative thoughts generating disturbing feelings, it drags down your mood.

It can make you feel terrible.

Have you ever been in a funk where you seem to emotionally vacillate between feeling a bit down and feeling really depressed?

Woody Allen said, “Most of the time I don’t have much fun. The rest of the time I don’t have any fun at all.”

That pretty much sums it up.

That is the ordinary existence for anyone who doesn’t employ mental rituals to alter their mood.

Weeding the garden of my mind

When I first started meditating in the float tank, I had no particular agenda other than to see what would happen, similar to John C. Lilly, the inventor of the float tank.

What I discovered frightened me.

There is an unfathomable amount of garbage fermenting in the subconscious mind.

When I discovered the reality of my own mind, I became motivated to clean it up. Once I realized I had thousands of poisonous thoughts taking root in my mind, I knew I had to do something.

Fortunately, I had been previously exposed to Tibetan Buddhist Lamrim, so I knew of a method for weeding my mental garden.

I devoted several hundred hours to practicing it.

It works.

The Voices in My Head

In the many, many hours of practice and focused awareness, I learned to parse the feelings in my subconscious mind and hear their voices. A casual reader might conclude I am psychotic, hallucinating my reality.

I am.

The consensus of modern neuroscience says I’m hallucinating Me.

This video is worth watching all the way through, many times over, to absorb its Truth.

When you read my descriptions of voices in my mind, these aren’t the loud, insistent voices of schizophrenia.

The mind processes feelings more than thoughts.

These feelings can be associated with voice, but often, it takes concentration on aptness to match voice to feeling. It’s like consulting a thesaurus. I know the right words when I feel them.

I can give voice to feelings if I can parse their effect from the chorus of feelings and thoughts in my mind.

It takes careful, mindful observation.

But I have no special gift. Anyone can learn this with enough time and focused concentration.

Existing as a disembodied mind in a float tank free from distractions certainly helps.

Me, Myself, and I

I no longer identified with my feelings and thoughts, but this realization only took me so far.

I knew what I was not, and that’s helpful information, but it didn’t really show me who or what I feel I am.

What made me, me, and not someone else?

The Act of Selfing

The conventions of English fail us in this area. Our minds are taught to instinctively think in terms of actors and actions, nouns and verbs.

For every act, there is an actor; for every effect, there is a cause; so the mind conceives of the “I” as something real and substantial, a detectable nugget that might show up in a science experiment.

That isn’t how I exist. There is no substantial self.

This may come as a shock to you, but you don’t exist in a substantive, “real” way at all.

In English, when we refer to an action as an actor, we use Gerunds.

We take an action, a verb, and we press it into service as an object, a noun.

That’s what you are: an action, a process, a construct of your mind.

You’re a Gerund.

You’re Selfing.

This video is quite long, but it will explain to you exactly how you exist, grounded in modern neuroscience.

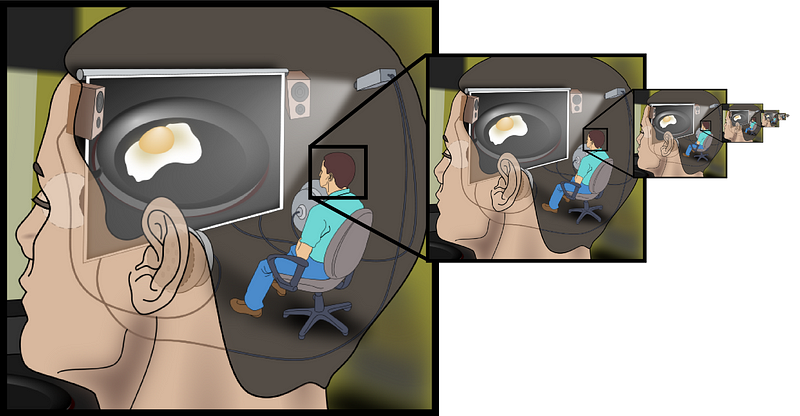

You and I exist as a field of perceptual awareness created by our brains and bodies.

Our body’s central nervous system sends signals to our brains, where it’s brought together as a real-time simulation, or best guess at conditions in the outside world.

It feels like the Inner Theater, but no Homunculus spoils the party.

Binding Action in the Brain

In an evolutionary environment where split-second decisions determine life and death, the mind can’t take time to hold a committee meeting to determine a course of action all our senses can agree upon.

If you were a mouse that needed to avoid a silent owl gliding through the sky, it would be life-ending to have the mind get a signal from the eyes that says “run” and a signal from the ears that says “no worries, keep eating” with no way to sort out what to do.

A creature without binding action would constantly respond to false signals from every sense, expending needless energy.

The calorie cost would likely result in starvation and death.

Binding action in the brain creates our subjective experience. It’s a necessary evolutionary reaction that allows organisms to make speedy reactions to environmental stimuli with a minimum of energy wasted on unnecessary actions.

The perceptual field of awareness

The binding action in the brain creates a perceptual field of awareness that encompasses all your sense data, with the gaps filled in by your mind’s expectations.

It’s rather astonishing to realize that most of our experience is not produced by the environment as we perceive it. Our brain takes a small amount of sensory information and fills in all the gaps with expectations based on prior experience. Our minds literally do create our reality.

This video details modern neuroscience’s understanding of how the brain creates our reality.

Most people identify with their perceptual field as the self.

My perceptual field is me.

Your perceptual field is you.

When that information goes in and generates that perceptual field, the information flow is only one way.

You and I can’t share perceptual fields. I can’t directly know your experience.

My mind is unknowable to you. An Ultimate Divide exists between our subjective experiences and the outside, objective world.

Subjective experience can never be shared. You can’t know What it’s like to be a bat or another human being.

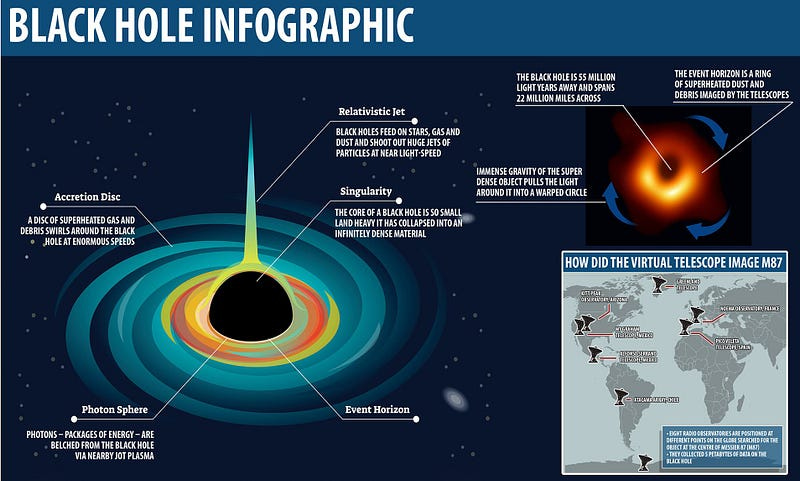

It’s like the information event horizon of a black hole; data only goes one way.

At the information event horizon of a black hole, whatever enters never returns.

We have no possible way of testing what happens beyond this barrier because no matter what test we run, no information to gather and analyze is ever forthcoming from the other side.

A bit like death.

Stop Selfing. Game Over.

You are in every way dependent upon your brain and body for your existence. Without them, no perceptual field is generated, and no selfing occurs.

Buddhists call this dependant arising.

This has a profound implication: Selfing doesn’t occur forever.

Selfing requires a brain and body in order to exist. When your body and brain fail, you cease to exist.

For an afterlife to be real, the ghost in our bio-machine must persist in some form that simulates body consciousness after death.

Which body do you get? A healthy, robust one of your youth? A decrepit and deteriorated body of old age? If you die in pain, do you experience that pain for eternity?

Your perception of reality depends on the brain and body, and at death, you no longer have either one.

This idea frightens some people, but if you reflect on it more deeply, it shouldn’t be so troubling on a personal level.

When my brain no longer generates consciousness, I am dead — but I won’t know it.

If it’s cold in the grave, I won’t be there to feel its sting.

I will no longer exist.

Selfing stops.

No lasting weeping and gnashing of teeth.

Some people become really distressed about this, believing it is contrary to their spiritual or religious beliefs, but I find it comforting.

There is an end to suffering—at least in this life.

I hope you find comfort in that too.

Relief of Emotional Pain and Suffering in This Life

My exploration of the mind and subsequent meditation practice have convinced me that we can achieve a significant diminishment of suffering in this life.

I am certain that the mind can be made more peaceful, which leads to greater joy and happiness.

The method I selected is the Buddhist meditation practice, specifically the Tibetan Buddhist Lamrim path. There may be other paths to salvation or cessation of suffering, but I can only attest to this one.

I've never tried the tank. It must be an interesting experience!